Siege of Candia

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (September 2011) |

| Siege of Candia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cretan War (Fifth Ottoman–Venetian War) | |||||||||

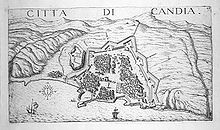

The siege of Candia by N. Visscher, c. 1680 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Ottoman Empire | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Köprülü Fazıl Ahmed | Francesco Morosini | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 118,754 soldiers (Venetian reports)[1] | 30,985 Venetian soldiers (Venetian reports)[1] | ||||||||

The siege of Candia (now Heraklion, Crete) was a military conflict in which Ottoman forces besieged the Venetian-ruled capital city of the Kingdom of Candia.[2] Lasting from 1648 to 1669, or a total of 21 years, one of the longest sieges in history. It ended with an Ottoman victory, but the effort and cost of the siege contributed to the decline of the Ottoman Empire, especially after the Great Turkish War.

Background

[edit]In the 17th century, Venice's power in the Mediterranean was waning as Ottoman power grew. The Republic of Venice believed that the Ottomans would use any excuse to pursue further hostilities.

In 1644, the Knights of Malta attacked an Ottoman convoy of sailing ships on its way from Constantinople to Alexandria. They landed at Candia with the loot, which included the former Chief Black Eunuch of the Harem, the kadi of Cairo, among other pilgrims heading to Mecca.

In response, 60,000 Ottoman troops led by Yusuf Pasha disembarked on Venetian Crete with no apparent target, with many suspecting them heading for Malta. Instead, the Ottomans surprisingly struck against Crete in June 1645, besieging and occupying La Canea (modern Chania) and Rettimo (modern Rethimno). Each of these cities took two months to be conquered. Between 1645 and 1648, the Ottomans occupied the rest of the island and prepared to take the capital, Candia.

Siege

[edit]

The siege of Candia began in May 1648. The Ottomans spent three months laying siege to the city, cutting off the water supply, and disrupting Venice's sea lanes to the city. They would bombard the city for the next 16 years to little effect.

The Venetians, in turn, sought to blockade the Ottoman-held Dardanelles to prevent the resupply of the Ottoman expeditionary force on Crete. This effort led to a series of naval actions. On 21 June 1655 and 26 August 1656, the Venetians were victorious, although the Venetian commander, Lorenzo Marcello, was killed in the latter engagement. However, on 17–19 July 1657, the Ottoman navy soundly defeated the Venetians. The Venetian captain, Lazzaro Mocenigo, was killed by a falling mast.

Venice received more aid from other western European states after the 7 November 1659 Treaty of the Pyrenees and the consequent peace between France and Spain. However, the Peace of Vasvár (August 1664) released additional Ottoman forces for action against the Venetians in Candia.

In 1666, a Venetian attempt to recapture La Canea failed. The following year, Colonel Andrea Barozzi, a Venetian military engineer, defected to the Ottomans and gave them information on weak spots in Candia's fortifications. On 24 July 1669, a French land/sea expedition under Francois de Beaufort not only failed to lift the siege, but also lost the fleet's vice-flagship La Thérèse, a 900-ton French warship armed with 58 cannons, to an accidental explosion. This dual disaster was devastating to the morale of the city's defenders.

Chastened by their failed relief effort and the loss of so valuable a warship, the French abandoned Candia in August 1669, leaving Captain General Francesco Morosini, the commander of Venetian forces, with only 3,600 fit men and scant supplies to defend the fortress. He, therefore, accepted terms and surrendered to Ahmed Köprülü, the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire on 27 September 1669. However, his surrender without first receiving authorization from the Venetian Senate made Morosini a controversial figure in Venice for some years afterward.

As part of the surrender terms, all Christians were allowed to leave Candia with whatever they could carry. At the same time, Venice retained possession of Gramvousa, Souda and Spinalonga, fortified islands that shielded natural harbors where Venetian ships could stop during their voyages to the eastern Mediterranean. After Candia's fall, the Venetians somewhat offset their defeat by expanding their holdings in Dalmatia.

Proposed biological warfare attack

[edit]Data obtained from the Archives of the Venetian State, relating to an operation organized by the Venetian Intelligence Services, describes a plan aimed at lifting the siege by infecting the Ottoman soldiers with plague; this was to be done by attacking them with a liquid made from the spleens and buboes of plague victims. "Although the plan was perfectly organized, and the deadly mixture was ready to use, the attack was ultimately never carried out."[3] According to a scholar from the USA's National Defense University, information about this planned attack was previously unknown to historians of biological warfare until published in December 2015.[4]

Other participants

[edit]- Knights of Malta fought at the siege of Candia (in Crete) in 1668

- François de Beaufort, who died there

- Philippe de Montaut-Bénac, marshal under the duke of Beaufort

- Philippe de Vendôme, the nephew of the duke of Beaufort

- Vincenzo Rospigliosi, admiral of the fleet and Pope Clement's nephew

- Georg Rimpler, German engineer

- Charles de Sévigné

- Louis de Buade de Frontenac

In fiction

[edit]The siege of Candia is an integral part of the background to the historical novel An Instance of the Fingerpost, where a significant protagonist is a Venetian veteran of that siege and several plot developments become clear through extensive flashbacks to the Candia events.

In season 6, episode 3 of the HBO series Silicon Valley, Gilfoyle (incorrectly) states that the Siege of Candia was only ended by use of biological warfare, where the Ottomans were defeated when they became infected with the plague-infested lymph nodes of the dead.

See also

[edit]- Naval battles of the Cretan Wars

- History of the Republic of Venice

- Ottoman Navy

- Ottoman wars in Europe

References

[edit]- ^ a b Paoletti, Ciro (2008). A Military History of Italy. p. 33.

- ^ Mason, Norman David (1972). The War of Candia, 1645–1669 (PhD). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. doi:10.31390/gradschool_disstheses.2351.

- ^ Thalassinou, Eleni; et al. (December 21, 2015). "Biological Warfare Plan in the 17th Century—the Siege of Candia, 1648–1669". Emerg Infect Dis. 21 (12): 2148–2153. doi:10.3201/eid2112.130822. PMC 4672449. PMID 26894254.

Citing public domain text from the CDC

- ^ Carus, W. Seth (September 2016). "Letter to the Editor-Biological Warfare in the 17th Century". Emerg Infect Dis. 22 (9): 1663–1664. doi:10.3201/eid2209.152073. PMC 4994373. PMID 27533653.

- The War for Candia, by the VENIVA consortium.

- Venice Republic: Renaissance Archived 2015-06-10 at the Wayback Machine, 1645–69 The war of Candia, by Marco Antonio Bragadin.

- The Cretan War – 1645–1669 by Chrysoula Tzompanaki (in Greek).

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (April 2009) |

- 1640s conflicts

- 1650s conflicts

- 1660s conflicts

- 17th century in Greece

- 1640s in the Ottoman Empire

- 1650s in the Ottoman Empire

- 1660s in the Ottoman Empire

- Kingdom of Candia

- Sieges involving the Ottoman Empire

- Sieges of the Ottoman–Venetian Wars

- Sieges involving the Republic of Venice

- Military history of Greece

- Heraklion

- Battles of the Cretan War (1645–1669)