Gulag

Trademark logo (1939)  Map of the camps between 1923 and 1961[a] | |

|

| Gulag | |

| Russian | ГУЛАГ |

|---|---|

| Romanization | Gulag |

| Literal meaning | Main Administration of Camps / General Authority of Camps |

| Mass repression in the Soviet Union |

|---|

| Economic repression |

| Political repression |

| Ideological repression |

| Ethnic repression |

| Politics of the Soviet Union |

|---|

|

|

|

The Gulag[c][d] was a system of forced labor camps in the Soviet Union.[10][11][9] The word Gulag originally referred only to the division of the Soviet secret police that was in charge of running the forced labor camps from the 1930s to the early 1950s during Joseph Stalin's rule, but in English literature the term is popularly used for the system of forced labor throughout the Soviet era. The abbreviation GULAG (ГУЛАГ) stands for "Гла́вное Управле́ние исправи́тельно-трудовы́х ЛАГере́й" (Main Directorate of Correctional Labour Camps), but the full official name of the agency changed several times.

The Gulag is recognized as a major instrument of political repression in the Soviet Union. The camps housed both ordinary criminals and political prisoners, a large number of whom were convicted by simplified procedures, such as NKVD troikas or other instruments of extrajudicial punishment. In 1918–1922, the agency was administered by the Cheka, followed by the GPU (1922–1923), the OGPU (1923–1934), later known as the NKVD (1934–1946), and the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD) in the final years. The Solovki prison camp, the first correctional labour camp which was constructed after the revolution, was opened in 1918 and legalized by a decree, "On the creation of the forced-labor camps", on April 15, 1919.

The internment system grew rapidly, reaching a population of 100,000 in the 1920s. By the end of 1940, the population of the Gulag camps amounted to 1.5 million.[12] The emergent consensus among scholars is that, of the 14 million prisoners who passed through the Gulag camps and the 4 million prisoners who passed through the Gulag colonies from 1930 to 1953, roughly 1.5 to 1.7 million prisoners perished there or died soon after they were released.[1][2][3] Some journalists and writers who question the reliability of such data heavily rely on memoir sources that come to higher estimations.[1][7] Archival researchers have found "no plan of destruction" of the gulag population and no statement of official intent to kill them, and prisoner releases vastly exceeded the number of deaths in the Gulag.[1] This policy can partially be attributed to the common practice of releasing prisoners who were suffering from incurable diseases as well as prisoners who were near death.[12][13]

Almost immediately after the death of Stalin, the Soviet establishment started to dismantle the Gulag system. A mass general amnesty was granted in the immediate aftermath of Stalin's death, but it was only offered to non-political prisoners and political prisoners who had been sentenced to a maximum of five years in prison. Shortly thereafter, Nikita Khrushchev was elected First Secretary, initiating the processes of de-Stalinization and the Khrushchev Thaw, triggering a mass release and rehabilitation of political prisoners. Six years later, on 25 January 1960, the Gulag system was officially abolished when the remains of its administration were dissolved by Khrushchev. The legal practice of sentencing convicts to penal labor continues to exist in the Russian Federation, but its capacity is greatly reduced.[14][15]

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, who survived eight years of Gulag incarceration, gave the term its international repute with the publication of The Gulag Archipelago in 1973. The author likened the scattered camps to "a chain of islands", and as an eyewitness, he described the Gulag as a system where people were worked to death.[16] In March 1940, there were 53 Gulag camp directorates (simply referred to as "camps") and 423 labor colonies in the Soviet Union.[4] Many mining and industrial towns and cities in northern Russia, eastern Russia and Kazakhstan such as Karaganda, Norilsk, Vorkuta and Magadan, were blocks of camps which were originally built by prisoners and subsequently run by ex-prisoners.[17]

Etymology

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2022) |

GULAG (ГУЛАГ) stands for "Гла́вное управле́ние испави́тельно-трудовы́х лагере́й" (Main Directorate of Correctional Labour Camps). It was renamed several times, e.g., to Main Directorate of Correctional Labor Colonies (Главное управление исправительно-трудовых колоний (ГУИТК)), which names can be seen in the documents describing the subordination of various camps.[18]

Overview

[edit]

Some historians estimate that 14 million people were imprisoned in the Gulag labor camps from 1929 to 1953 (the estimates for the period from 1918 to 1929 are more difficult to calculate).[19] Other calculations, by historian Orlando Figes, refer to 25 million prisoners of the Gulag in 1928–1953.[20] A further 6–7 million were deported and exiled to remote areas of the USSR, and 4–5 million passed through labor colonies, plus 3.5 million who were already in, or had been sent to, labor settlements.[19]

According to some estimates, the total population of the camps varied from 510,307 in 1934 to 1,727,970 in 1953.[4] According to other estimates, at the beginning of 1953 the total number of prisoners in prison camps was more than 2.4 million of which more than 465,000 were political prisoners.[21][22] Between the years 1934 to 1953, 20% to 40% of the Gulag population in each given year were released.[23][24]

The institutional analysis of the Soviet concentration system is complicated by the formal distinction between GULAG and GUPVI. GUPVI (ГУПВИ) was the Main Administration for Affairs of Prisoners of War and Internees (Главное управление по делам военнопленных и интернированных, [Glavnoye upravleniye po delam voyennoplennyh i internirovannyh] Error: {{Lang}}: invalid parameter: |label= (help)), a department of NKVD (later MVD) in charge of handling of foreign civilian internees and POWs (prisoners of war) in the Soviet Union during and in the aftermath of World War II (1939–1953). In many ways the GUPVI system was similar to GULAG.[25]

Its major function was the organization of foreign forced labor in the Soviet Union. The top management of GUPVI came from the GULAG system. The major memoir noted distinction from GULAG was the absence of convicted criminals in the GUPVI camps. Otherwise the conditions in both camp systems were similar: hard labor, poor nutrition and living conditions, and high mortality rate.[26]

For the Soviet political prisoners, like Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, all foreign civilian detainees and foreign POWs were imprisoned in the GULAG; the surviving foreign civilians and POWs considered themselves prisoners in the GULAG. According to the estimates, in total, during the whole period of the existence of the GUPVI, there were over 500 POW camps (within the Soviet Union and abroad), which imprisoned over 4,000,000 POW.[27] Most Gulag inmates were not political prisoners, although significant numbers of political prisoners could be found in the camps at any one time.[21]

Petty crimes and jokes about the Soviet government and officials were punishable by imprisonment.[28][29] About half of political prisoners in the Gulag camps were imprisoned "by administrative means", i.e., without trial at courts; official data suggest that there were over 2.6 million sentences to imprisonment on cases investigated by the secret police throughout 1921–53.[30] Maximum sentences varied depending on the type of crime and changed over time. From 1953, the maximum sentence for petty theft was six months,[31] having previously been one year and seven years. Theft of state property however, had a minimum sentence of seven years and a maximum of twenty five.[32] In 1958, the maximum sentence for any crime was reduced from twenty five to fifteen years.[33]

In 1960, the Ministerstvo Vnutrennikh Del (MVD) ceased to function as the Soviet-wide administration of the camps in favour of individual republic MVD branches. The centralised detention administrations temporarily ceased functioning.[34][35]

Contemporary usage of the word and the usage of other terms

[edit]

Although the term Gulag was originally used in reference to a government agency, in English and many other languages, the acronym acquired the qualities of a common noun, denoting the Soviet system of prison-based, unfree labor.[36]

Even more broadly, "Gulag" has come to mean the Soviet repressive system itself, the set of procedures that prisoners once called the "meat-grinder": the arrests, the interrogations, the transport in unheated cattle cars, the forced labor, the destruction of families, the years spent in exile, the early and unnecessary deaths.

Western authors use the term Gulag to denote all the prisons and internment camps in the Soviet Union. The term's contemporary usage is at times notably not directly related to the USSR, such as in the expression "North Korea's Gulag"[37] for camps operational today.[38]

The word Gulag was not often used in Russian, either officially or colloquially; the predominant terms were the camps (лагеря, lagerya) and the zone (зона, zona), usually singular, for the labor camp system and for the individual camps. The official term, "correctional labour camp", was suggested for official use by the Politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in the session of July 27, 1929.

History

[edit]Background

[edit]

The Tsar and the Russian Empire both used forced exile and forced labour as forms of judicial punishment. Katorga, a category of punishment which was reserved for those who were convicted of the most serious crimes, had many of the features which were associated with labor-camp imprisonment: confinement, simplified facilities (as opposed to the facilities which existed in prisons), and forced labor, usually involving hard, unskilled or semi-skilled work. According to historian Anne Applebaum, katorga was not a common sentence; approximately 6,000 katorga convicts were serving sentences in 1906 and 28,600 in 1916.[39] Under the Imperial Russian penal system, those who were convicted of less serious crimes were sent to corrective prisons and they were also made to work.[40]

Forced exile to Siberia had been in use for a wide range of offenses since the seventeenth century and it was a common punishment for political dissidents and revolutionaries. In the nineteenth century, the members of the failed Decembrist revolt and Polish nobles who resisted Russian rule were sent into exile. Fyodor Dostoevsky was sentenced to die for reading banned literature in 1849, but the sentence was commuted to banishment to Siberia. Members of various socialist revolutionary groups, including Bolsheviks such as Sergo Ordzhonikidze, Vladimir Lenin, Leon Trotsky, and Joseph Stalin were also sent into exile.[41]

Convicts who were serving labor sentences and exiles were sent to the underpopulated areas of Siberia and the Russian Far East – regions that lacked towns or food sources as well as organized transportation systems. Despite the isolated conditions, some prisoners successfully escaped to populated areas. Stalin himself escaped three of the four times after he was sent into exile.[42] Since these times, Siberia gained its fearful connotation as a place of punishment, a reputation which was further enhanced by the Soviet GULAG system. The Bolsheviks' own experiences with exile and forced labor provided them with a model which they could base their own system on, including the importance of strict enforcement.

From 1920 to 1950, the leaders of the Communist Party and the Soviet state considered repression a tool that they should use to secure the normal functioning of the Soviet state system and preserve and strengthen their positions within their social base, the working class (when the Bolsheviks took power, peasants represented 80% of the population).[43]

In the midst of the Russian Civil War, Lenin and the Bolsheviks established a "special" prison camp system, separate from its traditional prison system and under the control of the Cheka.[44] These camps, as Lenin envisioned them, had a distinctly political purpose.[45] These early camps of the GULAG system were introduced in order to isolate and eliminate class-alien, socially dangerous, disruptive, suspicious, and other disloyal elements, whose deeds and thoughts were not contributing to the strengthening of the dictatorship of the proletariat.[43]

Forced labor as a "method of reeducation" was applied in the Solovki prison camp as early as the 1920s,[46] based on Trotsky's experiments with forced labor camps for Czech war prisoners from 1918 and his proposals to introduce "compulsory labor service" voiced in Terrorism and Communism.[46][47] These concentration camps were not identical to the Stalinist or Hitler camps, but were introduced to isolate war prisoners given the extreme historical situation following World War 1.[48]

Various categories of prisoners were defined: petty criminals, POWs of the Russian Civil War, officials accused of corruption, sabotage and embezzlement, political enemies, dissidents and other people deemed dangerous for the state. In the first decade of Soviet rule, the judicial and penal systems were neither unified nor coordinated, and there was a distinction between criminal prisoners and political or "special" prisoners.

The "traditional" judicial and prison system, which dealt with criminal prisoners, were first overseen by The People's Commissariat of Justice until 1922, after which they were overseen by the People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs, also known as the NKVD.[49] The Cheka and its successor organizations, the GPU or State Political Directorate and the OGPU, oversaw political prisoners and the "special" camps to which they were sent.[50] In April 1929, the judicial distinctions between criminal and political prisoners were eliminated, and control of the entire Soviet penal system turned over to the OGPU.[51] In 1928, there were 30,000 individuals interned; the authorities were opposed to compelled labor. In 1927, the official in charge of prison administration wrote:

The exploitation of prison labour, the system of squeezing "golden sweat" from them, the organisation of production in places of confinement, which while profitable from a commercial point of view is fundamentally lacking in corrective significance – these are entirely inadmissible in Soviet places of confinement.[52]

The legal base and the guidance for the creation of the system of "corrective labor camps" (исправи́тельно-трудовые лагеря, Ispravitel'no-trudovye lagerya), the backbone of what is commonly referred to as the "Gulag", was a secret decree from the Sovnarkom of July 11, 1929, about the use of penal labor that duplicated the corresponding appendix to the minutes of the Politburo meeting of June 27, 1929.[citation needed][53]

One of the Gulag system founders was Naftaly Frenkel. In 1923, he was arrested for illegally crossing borders and smuggling. He was sentenced to 10 years' hard labor at Solovki, which later came to be known as the "first camp of the Gulag". While serving his sentence he wrote a letter to the camp administration detailing a number of "productivity improvement" proposals including the infamous system of labor exploitation whereby the inmates' food rations were to be linked to their rate of production, a proposal known as nourishment scale (шкала питания). This notorious you-eat-as-you-work system would often kill weaker prisoners in weeks and caused countless casualties. The letter caught the attention of a number of high communist officials including Genrikh Yagoda and Frenkel soon went from being an inmate to becoming a camp commander and an important Gulag official. His proposals soon saw widespread adoption in the Gulag system.[54]

After having appeared as an instrument and place for isolating counter-revolutionary and criminal elements, the Gulag, because of its principle of "correction by forced labor", quickly became, in fact, an independent branch of the national economy secured on the cheap labor force presented by prisoners. Hence it is followed by one more important reason for the constancy of the repressive policy, namely, the state's interest in unremitting rates of receiving a cheap labor force that was forcibly used, mainly in the extreme conditions of the east and north.[43] The Gulag possessed both punitive and economic functions.[55]

Formation and expansion under Stalin

[edit]The Gulag was an administration body that watched over the camps; eventually its name would be used for these camps retrospectively. After Lenin's death in 1924, Stalin was able to take control of the government, and began to form the gulag system. On June 27, 1929, the Politburo created a system of self-supporting camps that would eventually replace the existing prisons around the country.[56] These prisons were meant to receive inmates that received a prison sentence that exceeded three years. Prisoners who had a shorter prison sentence than three years were to remain in the prison system that was still under the purview of the NKVD.

The purpose of these new camps was to colonise the remote and inhospitable environments throughout the Soviet Union. These changes took place around the same time that Stalin started to institute collectivisation and rapid industrial development. Collectivisation resulted in a large scale purge of peasants and so-called Kulaks. The Kulaks were supposedly wealthy, comparatively to other Soviet peasants, and were considered to be capitalists by the state, and by extension enemies of socialism. The term would also become associated with anyone who opposed or even seemed unsatisfied with the Soviet government.

By late 1929, Stalin began a program known as dekulakization. Stalin demanded that the kulak class be completely wiped out, resulting in the imprisonment and execution of Soviet peasants. In a mere four months, 60,000 people were sent to the camps and another 154,000 exiled. This was only the beginning of the dekulakisation process, however. In 1931 alone, 1,803,392 people were exiled.[57]

Although these massive relocation processes were successful in getting a large potential free forced labor work force where they needed to be, that is about all it was successful at doing. The "special settlers", as the Soviet government referred to them, all lived on starvation level rations, and many people starved to death in the camps, and anyone who was healthy enough to escape tried to do just that. This resulted in the government having to give rations to a group of people they were getting hardly any use out of, and was just costing the Soviet government money. The Unified State Political Administration (OGPU) quickly realised the problem, and began to reform the dekulakisation process.[58]

To help prevent the mass escapes the OGPU started to recruit people within the colony to help stop people who attempted to leave, and set up ambushes around known popular escape routes. The OGPU also attempted to raise the living conditions in these camps that would not encourage people to actively try and escape, and Kulaks were promised that they would regain their rights after five years. Even these revisions ultimately failed to resolve the problem, and the dekulakisation process was a failure in providing the government with a steady forced labor force. These prisoners were also lucky to be in the gulag in the early 1930s. Prisoners were relatively well off compared to what the prisoners would have to go through in the final years of the gulag.[58] The Gulag was officially established on April 25, 1930, as the GULAG by the OGPU order 130/63 in accordance with the Sovnarkom order 22 p. 248 dated April 7, 1930. It was renamed as the GULAG in November of that year.[59]

The hypothesis that economic considerations were responsible for mass arrests during the period of Stalinism has been refuted on the grounds of former Soviet archives that have become accessible since the 1990s, although some archival sources also tend to support an economic hypothesis.[60][61] In any case, the development of the camp system followed economic lines. The growth of the camp system coincided with the peak of the Soviet industrialisation campaign. Most of the camps established to accommodate the masses of incoming prisoners were assigned distinct economic tasks.[citation needed] These included the exploitation of natural resources and the colonization of remote areas, as well as the realisation of enormous infrastructural facilities and industrial construction projects. The plan to achieve these goals with "special settlements" instead of labor camps was dropped after the revealing of the Nazino affair in 1933.

The 1931–32 archives indicate the Gulag had approximately 200,000 prisoners in the camps; while in 1935, approximately 800,000 were in camps and 300,000 in colonies.[62] Gulag population reached a peak value (1.5 million) in 1941, gradually decreased during the war and then started to grow again, achieving a maximum by 1953.[4] Besides Gulag camps, a significant amount of prisoners, which confined prisoners serving short sentence terms.[4]

In the early 1930s, a tightening of the Soviet penal policy caused a significant growth of the prison camp population.[63]

During the Great Purge of 1937–38, mass arrests caused another increase in inmate numbers. Hundreds of thousands of persons were arrested and sentenced to long prison terms on the grounds of one of the multiple passages of the notorious Article 58 of the Criminal Codes of the Union republics, which defined punishment for various forms of "counterrevolutionary activities". Under NKVD Order No. 00447, tens of thousands of Gulag inmates were executed in 1937–38 for "continuing counterrevolutionary activities".

Between 1934 and 1941, the number of prisoners with higher education increased more than eight times, and the number of prisoners with high education increased five times.[43] It resulted in their increased share in the overall composition of the camp prisoners.[43] Among the camp prisoners, the number and share of the intelligentsia was growing at the quickest pace.[43] Distrust, hostility, and even hatred for the intelligentsia was a common characteristic of the Soviet leaders.[43] Information regarding the imprisonment trends and consequences for the intelligentsia derive from the extrapolations of Viktor Zemskov from a collection of prison camp population movements data.[43][64]

During World War II

[edit]Political role

[edit]On the eve of World War II, Soviet archives indicate a combined camp and colony population upwards of 1.6 million in 1939, according to V. P. Kozlov.[62] Anne Applebaum and Steven Rosefielde estimate that 1.2 to 1.5 million people were in Gulag system's prison camps and colonies when the war started.[65][66]

After the German invasion of Poland that marked the start of World War II in Europe, the Soviet Union invaded and annexed eastern parts of the Second Polish Republic. In 1940, the Soviet Union occupied Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Bessarabia (now the Republic of Moldova) and Bukovina. According to some estimates, hundreds of thousands of Polish citizens[67][68] and inhabitants of the other annexed lands, regardless of their ethnic origin, were arrested and sent to the Gulag camps. However, according to the official data, the total number of sentences for political and anti-state (espionage, terrorism) crimes in the USSR in 1939–41 was 211,106.[30]

Approximately 300,000 Polish prisoners of war were captured by the USSR during and after the "Polish Defensive War".[69] Almost all of the captured officers and a large number of ordinary soldiers were then murdered (see Katyn massacre) or sent to Gulag.[70] Of the 10,000–12,000 Poles sent to Kolyma in 1940–41, most prisoners of war, only 583 men survived, released in 1942 to join the Polish Armed Forces in the East.[71] Out of General Anders' 80,000 evacuees from Soviet Union gathered in Great Britain only 310 volunteered to return to Soviet-controlled Poland in 1947.[72]

During the Great Patriotic War, Gulag populations declined sharply due to a steep rise in mortality in 1942–43. In the winter of 1941, a quarter of the Gulag's population died of starvation.[73] 516,841 prisoners died in prison camps in 1941–43,[74][75] from a combination of their harsh working conditions and the famine caused by the German invasion. This period accounts for about half of all gulag deaths, according to Russian statistics.

In 1943, the term katorga works (каторжные работы) was reintroduced. They were initially intended for Nazi collaborators, but then other categories of political prisoners (for example, members of deported peoples who fled from exile) were also sentenced to "katorga works". Prisoners sentenced to "katorga works" were sent to Gulag prison camps with the most harsh regime and many of them perished.[75]

Economic role

[edit]

Up until World War II, the Gulag system expanded dramatically to create a Soviet "camp economy". Right before the war, forced labor provided 46.5% of the nation's nickel, 76% of its tin, 40% of its cobalt, 40.5% of its chrome-iron ore, 60% of its gold, and 25.3% of its timber.[76] And in preparation for war, the NKVD put up many more factories and built highways and railroads.

The Gulag quickly switched to the production of arms and supplies for the army after fighting began. At first, transportation remained a priority. In 1940, the NKVD focused most of its energy on railroad construction.[77] This would prove extremely important when the German advance into the Soviet Union started in 1941. In addition, factories converted to produce ammunition, uniforms, and other supplies. Moreover, the NKVD gathered skilled workers and specialists from throughout the Gulag into 380 special colonies which produced tanks, aircraft, armaments, and ammunition.[76]

Despite its low capital costs, the camp economy suffered from serious flaws. For one, actual productivity almost never matched estimates: the estimates proved far too optimistic. In addition, scarcity of machinery and tools plagued the camps and the tools that the camps did have quickly broke. The Eastern Siberian Trust of the Chief Administration of Camps for Highway Construction destroyed ninety-four trucks in just three years.[76] But the greatest problem was simple – forced labor was less efficient than free labor. In fact, prisoners in the Gulag were, on average, half as productive as free laborers in the USSR at the time,[76] which may be partially explained by malnutrition.

To make up for this disparity, the NKVD worked prisoners harder than ever. To meet rising demand, prisoners worked longer and longer hours, and on lower food-rations than ever before. A camp administrator said in a meeting: "There are cases when a prisoner is given only four or five hours out of twenty-four for rest, which significantly lowers his productivity." In the words of a former Gulag prisoner: "By the spring of 1942, the camp ceased to function. It was difficult to find people who were even able to gather firewood or bury the dead."[76]

The scarcity of food stemmed in part from the general strain on the entire Soviet Union, but also the lack of central aid to the Gulag during the war. The central government focused all its attention on the military and left the camps to their own devices. In 1942, the Gulag set up the Supply Administration to find their own food and industrial goods. During this time, not only did food become scarce, but the NKVD limited rations in an attempt to motivate the prisoners to work harder for more food, a policy that lasted until 1948.[78]

In addition to food shortages, the Gulag suffered from labor scarcity at the beginning of the war. The Great Terror of 1936–1938 had provided a large supply of free labor, but by the start of World War II the purges had slowed down. In order to complete all of their projects, camp administrators moved prisoners from project to project.[77] To improve the situation, laws were implemented in mid-1940 that allowed giving short camp sentences (4 months or a year) to those convicted of petty theft, hooliganism, or labor-discipline infractions. By January 1941, the Gulag workforce had increased by approximately 300,000 prisoners.[77] But in 1942, serious food shortages began, and camp populations dropped again. The camps lost still more prisoners to the war effort as the Soviet Union went into a total war footing in June 1941. Many laborers received early releases so that they could be drafted and sent to the front.[78]

Even as the pool of workers shrank, demand for outputs continued to grow rapidly. As a result, the Soviet government pushed the Gulag to "do more with less". With fewer able-bodied workers and few supplies from outside the camp system, camp administrators had to find a way to maintain production. The solution they found was to push the remaining prisoners still harder. The NKVD employed a system of setting unrealistically high production goals, straining resources in an attempt to encourage higher productivity. As the Axis armies pushed into Soviet territory from June 1941 on, labor resources became further strained, and many of the camps had to evacuate out of Western Russia.[78]

From the beginning of the war to halfway through 1944, 40 camps were set up, and 69 were disbanded. During evacuations, machinery received priority, leaving prisoners to reach safety on foot. The speed of Operation Barbarossa's advance prevented the evacuation of all prisoners in good time, and the NKVD massacred many to prevent them from falling into German hands. While this practice denied the Germans a source of free labor, it also further restricted the Gulag's capacity to keep up with the Red Army's demands. When the tide of the war turned, however, and the Soviets started pushing the Axis invaders back, fresh batches of laborers replenished the camps. As the Red Army recaptured territories from the Germans, an influx of Soviet ex-POWs greatly increased the Gulag population.[78]

After World War II

[edit]

After World War II, the number of inmates in prison camps and colonies sharply rose again, reaching approximately 2.5 million people by the early 1950s (about 1.7 million of whom were in camps).

When the war in Europe ended in May 1945, as many as two million former Russian citizens were forcefully repatriated into the USSR.[79] On February 11, 1945, at the conclusion of the Yalta Conference, the United States and United Kingdom signed a Repatriation Agreement with the Soviet Union.[80] One interpretation of this agreement resulted in the forcible repatriation of all Soviets. British and United States civilian authorities ordered their military forces in Europe to deport to the Soviet Union up to two million former residents of the Soviet Union, including persons who had left the Russian Empire and established different citizenship years before. The forced repatriation operations took place from 1945 to 1947.[81]

Multiple sources state that Soviet POWs, on their return to the Soviet Union, were treated as traitors (see Order No. 270).[82][83][84] According to some sources, over 1.5 million surviving Red Army soldiers imprisoned by the Germans were sent to the Gulag.[85][86][87] However, that is a confusion with two other types of camps. During and after World War II, freed POWs went to special "filtration" camps. Of these, by 1944, more than 90 percent were cleared, and about 8 percent were arrested or condemned to penal battalions. In 1944, they were sent directly to reserve military formations to be cleared by the NKVD.

Furthermore, in 1945, about 100 filtration camps were set for repatriated Ostarbeiter, POWs, and other displaced persons, which processed more than 4,000,000 people. By 1946, the major part of the population of these camps were cleared by NKVD and either sent home or conscripted (see table for details).[88] 226,127 out of 1,539,475 POWs were transferred to the NKVD, i.e. the Gulag.[88][89]

| Category | Total | % | Civilian | % | POWs | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Released and sent home[e] | 2,427,906 | 57.81 | 2,146,126 | 80.68 | 281,780 | 18.31 |

| Conscripted | 801,152 | 19.08 | 141,962 | 5.34 | 659,190 | 42.82 |

| Sent to labor battalions of the Ministry of Defence | 608,095 | 14.48 | 263,647 | 9.91 | 344,448 | 22.37 |

| Sent to NKVD as spetskontingent[f] (i.e. sent to GULAG) | 272,867 | 6.50 | 46,740 | 1.76 | 226,127 | 14.69 |

| Were waiting for transportation and worked for Soviet military units abroad | 89,468 | 2.13 | 61,538 | 2.31 | 27,930 | 1.81 |

| Total | 4,199,488 | 100 | 2,660,013 | 100 | 1,539,475 | 100 |

After Nazi Germany's defeat, ten NKVD-run "special camps" subordinate to the Gulag were set up in the Soviet Occupation Zone of post-war Germany. These "special camps" were former Stalags, prisons, or Nazi concentration camps such as Sachsenhausen (special camp number 7) and Buchenwald (special camp number 2). According to German government estimates "65,000 people died in those Soviet-run camps or in transportation to them."[90] According to German researchers, Sachsenhausen, where 12,500 Soviet era victims have been uncovered, should be seen as an integral part of the Gulag system.[91]

Yet the major reason for the post-war increase in the number of prisoners was the tightening of legislation on property offences in summer 1947 (at this time there was a famine in some parts of the Soviet Union, claiming about 1 million lives), which resulted in hundreds of thousands of convictions to lengthy prison terms, sometimes on the basis of cases of petty theft or embezzlement. At the beginning of 1953, the total number of prisoners in prison camps was more than 2.4 million of which more than 465,000 were political prisoners.[75]

In 1948, the system of "special camps" was established exclusively for a "special contingent" of political prisoners, convicted according to the more severe sub-articles of Article 58 (Enemies of people): treason, espionage, terrorism, etc., for various real political opponents, such as Trotskyites, "nationalists" (Ukrainian nationalism), white émigré, as well as for fabricated ones.

The state continued to maintain the extensive camp system for a while after Stalin's death in March 1953, although the period saw the grip of the camp authorities weaken, and a number of conflicts and uprisings occur (see Bitch Wars; Kengir uprising; Vorkuta uprising).

The amnesty of 1953 was limited to non-political prisoners and for political prisoners sentenced to not more than 5 years, therefore mostly those convicted for common crimes were then freed. The release of political prisoners started in 1954 and became widespread, and also coupled with mass rehabilitations, after Nikita Khrushchev's denunciation of Stalinism in his Secret Speech at the 20th Congress of the CPSU in February 1956.

The Gulag institution was closed by the MVD order No 020 of January 25, 1960,[59] but forced labor colonies for political and criminal prisoners continued to exist. Political prisoners continued to be kept in one of the most famous camps Perm-36[92] until 1987 when it was closed.[93]

The Russian penal system, despite reforms and a reduction in prison population, informally or formally continues many practices endemic to the Gulag system, including forced labor, inmates policing inmates, and prisoner intimidation.[15]

In the late 2000s, some human rights activists accused authorities of gradual removal of Gulag remembrance from places such as Perm-36 and Solovki prison camp.[94]

According to Encyclopædia Britannica,

At its height the Gulag consisted of many hundreds of camps, with the average camp holding 2,000–10,000 prisoners. Most of these camps were "corrective labour colonies" in which prisoners felled timber, laboured on general construction projects (such as the building of canals and railroads), or worked in mines. Most prisoners laboured under the threat of starvation or execution if they refused. It is estimated that the combination of very long working hours, harsh climatic and other working conditions, inadequate food, and summary executions killed tens of thousands of prisoners each year. Western scholarly estimates of the total number of deaths in the Gulag in the period from 1918 to 1956 ranged from 1.2 to 1.7 million.[95]

Death toll

[edit]Prior to the dissolution of the Soviet Union, estimates of Gulag victims ranged from 2.3 to 17.6 million (see History of Gulag population estimates). Mortality in Gulag camps in 1934–40 was 4–6 times higher than average in the Soviet Union. Post-1991 research by historians accessing archival materials brought this range down considerably.[96][97] In a 1993 study of archival Soviet data, a total of 1,053,829 people died in the Gulag from 1934 to 1953.[4]: 1024

It was common practice to release prisoners who were either suffering from incurable diseases or near death,[12][13] so a combined statistics on mortality in the camps and mortality caused by the camps was higher. The tentative historical consensus is that, of the 18 million people who passed through the gulag from 1930 to 1953, between 1.6 million[2][3] and 1.76 million[98] perished as a result of their detention,[1] and about half of all deaths occurred between 1941 and 1943 following the German invasion.[98][99] Timothy Snyder writes that "with the exception of the war years, a very large majority of people who entered the Gulag left alive".[100] If prisoner deaths from labor colonies and special settlements are included, the death toll rises to 2,749,163, according to J. Otto Pohl's incomplete data.[13][5]

In her 2018 study, Golfo Alexopoulos attempted to challenge this consensus figure by encompassing those whose life was shortened due to GULAG conditions.[1] Alexopoulos concluded from her research that a systematic practice of the Gulag was to release sick prisoners on the verge of death; and that all prisoners who received the health classification "invalid", "light physical labor", "light individualised labor", or "physically defective" that together according to Alexopoulos encompassed at least one third of all inmates who passed through the Gulag died or had their lives shortened due to detention in the Gulag in captivity or shortly after release.[101]

The GULAG mortality estimated in this way yields the figure of 6 million deaths.[6] Historian Orlando Figes and Russian writer Vadim Erlikman have posited similar estimates.[7][8] The estimate of Alexopoulos, however, has obvious methodological difficulties[1] and is supported by misinterpreted evidence, such as presuming that hundreds of thousands of prisoners "directed to other places of detention" in 1948 was a euphemism for releasing prisoners on the verge of death into labor colonies, when it was really referring to internal transport in the Gulag rather than release.[102]

In a University of Oxford doctoral dissertation, in 2020, the problem of medical release ('aktirovka') and of mortality among 'certified invalids' ('aktirovannye') was considered in detail by Mikhail Nakonechnyi. He concluded that the number of terminally ill people discharged early on medical grounds from the Gulag was about 1 million. Mikhail added 800,000–850,000 excess deaths to the death toll directly caused by the results of GULAG incarceration, which brings the death toll to 2.5 million people.[103]

Mortality rate

[edit]In 2009, Steven Rosefielde stated more complete archival data increases camp deaths by 19.4 percent to 1,258,537, "the best archivally-based estimate of Gulag excess deaths at present is 1.6 million from 1929 to 1953."[3] Dan Healey in 2018 also stated the same thing "New studies using declassified Gulag archives have provisionally established a consensus on mortality and "inhumanity." The tentative consensus says that once secret records of the Gulag administration in Moscow show a lower death toll than expected from memoir sources, generally between 1.5 and 1.7 million (out of 18 million who passed through) for the years from 1930 to 1953."[104]

Certificates of death in the Gulag system for the period from 1930 to 1956[105]

| Year | Deaths | Mortality rate % |

|---|---|---|

| 1930 | 7,980 | 4.20 |

| 1931 | 7,283 | 2.90 |

| 1932 | 13,197 | 4.80 |

| 1933 | 67,297 | 15.30 |

| 1934 | 25,187 | 4.28 |

| 1935 | 31,636 | 2.75 |

| 1936 | 24,993 | 2.11 |

| 1937 | 31,056 | 2.42 |

| 1938 | 108,654 | 5.35 |

| 1939 | 44,750 | 3.10 |

| 1940 | 41,275 | 2.72 |

| 1941 | 115,484 | 6.10 |

| 1942 | 352,560 | 24.90 |

| 1943 | 267,826 | 22.40 |

| 1944 | 114,481 | 9.20 |

| 1945 | 81,917 | 5.95 |

| 1946 | 30,715 | 2.20 |

| 1947 | 66,830 | 3.59 |

| 1948 | 50,659 | 2.28 |

| 1949 | 29,350 | 1.21 |

| 1950 | 24,511 | 0.95 |

| 1951 | 22,466 | 0.92 |

| 1952 | 20,643 | 0.84 |

| 1953 | 9,628 | 0.67 |

| 1954 | 8,358 | 0.69 |

| 1955 | 4,842 | 0.53 |

| 1956 | 3,164 | 0.40 |

| Total | 1,606,748 | 8.88 |

Gulag administrators

[edit]| Name | Years[106][107][108] |

|---|---|

| Feodor (Teodors) Ivanovich Eihmans | April 25, 1930 – June 16, 1930 |

| Lazar Iosifovich Kogan | June 16, 1930 – June 9, 1932 |

| Matvei Davidovich Berman | June 9, 1932 – August 16, 1937 |

| Israel Israelevich Pliner | August 16, 1937 – November 16, 1938 |

| Gleb Vasilievich Filaretov | November 16, 1938 – February 18, 1939 |

| Vasili Vasilievich Chernyshev | February 18, 1939 – February 26, 1941 |

| Victor Grigorievich Nasedkin | February 26, 1941 – September 2, 1947 |

| Georgy Prokopievich Dobrynin | September 2, 1947 – January 31, 1951 |

| Ivan Ilich Dolgikh | January 31, 1951 – October 5, 1954 |

| Sergei Yegorovich Yegorov | October 5, 1954 – April 4, 1956 |

Conditions

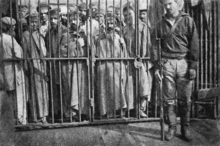

[edit]Living and working conditions in the camps varied significantly across time and place, depending, among other things, on the impact of broader events (World War II, countrywide famines and shortages, waves of terror, sudden influx or release of large numbers of prisoners) and the type of crime committed. Instead of being used for economic gain, political prisoners were typically given the worst work or were dumped into the less productive parts of the gulag. For example Victor Herman, in his memoirs, compares the Burepolom and the Nuksha 2 camps, which were both near Vyatka.[109][110]

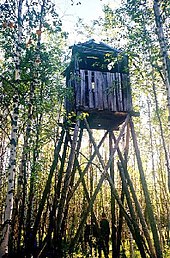

In Burepolom there were roughly 3,000 prisoners, all non-political, in the central compound. They could walk around at will, were lightly guarded, had unlocked barracks with mattresses and pillows, and watched western movies[clarification needed]. However Nuksha 2, which housed serious criminals and political prisoners, featured guard towers with machine guns and locked barracks.[110] In some camps prisoners were only permitted to send one letter a year and were not allowed to have photos of loved ones.[111]

Some prisoners were released early if they displayed good performance.[110] There were several productive activities for prisoners in the camps. For example, in early 1935, a course in livestock raising was held for prisoners at a state farm; those who took it had their workday reduced to four hours.[110] During that year the professional theater group in the camp complex gave 230 performances of plays and concerts to over 115,000 spectators.[110] Camp newspapers also existed.[110]

Andrei Vyshinsky, chief procurator of the Soviet Union, wrote a memorandum to NKVD chief Nikolai Yezhov in 1938, during the Great Purge, which stated:[112]

Among the prisoners there are some so ragged and lice-ridden that they pose a sanitary danger to the rest. These prisoners have deteriorated to the point of losing any resemblance to human beings. Lacking food…they collect orts [refuse] and, according to some prisoners, eat rats and dogs.

According to prisoner Yevgenia Ginzburg, Gulag inmates could tell when Yezhov was no longer in charge as one day the conditions relaxed. A few days later Beria's name appeared in official prison notices.[113]

In general, the central administrative bodies showed a discernible interest in maintaining the labor force of prisoners in a condition allowing the fulfilment of construction and production plans handed down from above. Besides a wide array of punishments for prisoners refusing to work (which, in practice, were sometimes applied to prisoners that were too enfeebled to meet production quota), they instituted a number of positive incentives intended to boost productivity. These included monetary bonuses (since the early 1930s) and wage payments (from 1950 onward), cuts of individual sentences, general early-release schemes for norm fulfilment and overfulfilment (until 1939, again in selected camps from 1946 onward), preferential treatment, sentence reduction and privileges for the most productive workers (shock workers or Stakhanovites in Soviet parlance).[114][110]

Inmates were used as camp guards and could purchase camp newspapers as well as bonds. Robert W. Thurston writes that this was "at least an indication that they were still regarded as participants in society to some degree."[110] Sports team, particularly football teams, were set up by the prison authorities.[115]

Boris Sulim, a former prisoner who had worked in the Omsuchkan camp, close to Magadan, when he was a teenager stated:[116]

I was 18 years old and Magadan seemed a very romantic place to me. I got 880 rubles a month and a 3000 ruble installation grant, which was a hell of a lot of money for a kid like me. I was able to give my mother some of it. They even gave me membership in the Komsomol. There was a mining and ore-processing plant which sent out parties to dig for tin. I worked at the radio station which kept contact with the parties. [...] If the inmates were good and disciplined they had almost the same rights as the free workers. They were trusted and they even went to the movies. As for the reason they were in the camps, well, I never poked my nose into details. We all thought the people were there because they were guilty.

Immediately after the German attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941 the conditions in camps worsened drastically: quotas were increased, rations cut, and medical supplies came close to none, all of which led to a sharp increase in mortality. The situation slowly improved in the final period and after the end of the war.

Considering the overall conditions and their influence on inmates, it is important to distinguish three major strata of Gulag inmates:

- Kulaks, osadniks, ukazniks (people sentenced for violation of various ukases, e.g. Law of Spikelets, decree about work discipline, etc.), occasional violators of criminal law

- Dedicated criminals: "thieves in law"

- People sentenced for various political and religious reasons.

Gulag and famine (1932–1933)

[edit]The Soviet famine of 1932–1933 swept across many different regions of the Soviet Union. During this time, it is estimated that around six to seven million people starved to death.[117] On 7 August 1932, a new decree drafted by Stalin (Law of Spikelets) specified a minimum sentence of ten years or execution for theft from collective farms or of cooperative property. Over the next few months, prosecutions rose fourfold. A large share of cases prosecuted under the law were for the theft of small quantities of grain worth less than fifty rubles. The law was later relaxed on 8 May 1933.[118] Overall, during the first half of 1933, prisons saw more new incoming inmates than the three previous years combined.

Prisoners in the camps faced harsh working conditions. One Soviet report stated that, in early 1933, up to 15% of the prison population in Soviet Uzbekistan died monthly. During this time, prisoners were getting around 300 calories (1,300 kJ) worth of food a day. Many inmates attempted to flee, causing an upsurge in coercive and violent measures. Camps were directed "not to spare bullets".[119]

Social conditions

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2014) |

The convicts in such camps were actively involved in all kinds of labor with one of them being logging. The working territory of logging presented by itself a square and was surrounded by forest clearing. Thus, all attempts to exit or escape from it were well observed from the four towers set at each of its corners.

Locals who captured a runaway were given rewards.[120] It is also said that camps in colder areas were less concerned with finding escaped prisoners as they would die anyhow from the severely cold winters. In such cases prisoners who did escape without getting shot were often found dead kilometres away from the camp.

Geography

[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2007) |

In the early days of Gulag, the locations for the camps were chosen primarily for the isolated conditions involved. Remote monasteries in particular were frequently reused as sites for new camps. The site on the Solovetsky Islands in the White Sea is one of the earliest and also most noteworthy, taking root soon after the Revolution in 1918.[16] The colloquial name for the islands, "Solovki", entered the vernacular as a synonym for the labor camp in general. It was presented to the world as an example of the new Soviet method for "re-education of class enemies" and reintegrating them through labor into Soviet society. Initially the inmates, largely Russian intelligentsia, enjoyed relative freedom within the natural confinement of the islands.[121]

Local newspapers and magazines were published. Even some scientific research was carried out, e.g., a local botanical garden was maintained but unfortunately later lost completely. Eventually, Solovki turned into an ordinary Gulag camp. Some historians maintain that it was a pilot camp of this type. In 1929, Maxim Gorky visited the camp and published an apology for it. The report of Gorky's trip to Solovki was included in the cycle of impressions titled "Po Soiuzu Sovetov", Part V, subtitled "Solovki." In the report, Gorky wrote that "camps such as 'Solovki' were absolutely necessary."[121]

With the new emphasis on Gulag as the means of concentrating cheap labor, new camps were then constructed throughout the Soviet sphere of influence, wherever the economic task at hand dictated their existence, or was designed specifically to avail itself of them, such as the White Sea–Baltic Canal or the Baikal–Amur Mainline, including facilities in big cities — parts of the famous Moscow Metro and the Moscow State University new campus were built by forced labor. Many more projects during the rapid industrialisation of the 1930s, war-time and post-war periods were fulfilled on the backs of convicts. The activity of Gulag camps spanned a wide cross-section of Soviet industry. Gorky organized in 1933 a trip of 120 writers and artists to the White Sea–Baltic Canal, 36 of them wrote a propaganda book about the construction published in 1934 and destroyed in 1937.

The majority of Gulag camps were positioned in extremely remote areas of northeastern Siberia (the best known clusters are Sevvostlag (The North-East Camps) along Kolyma river and Norillag near Norilsk) and in the southeastern parts of the Soviet Union, mainly in the steppes of Kazakhstan (Luglag, Steplag, Peschanlag). A detailed map was made by the Memorial Foundation.[122]

These were vast and sparsely inhabited regions with no roads or sources of food, but rich in minerals and other natural resources, such as timber. The construction of the roads was assigned to the inmates of specialised railway camps. Camps were generally spread throughout the entire Soviet Union, including the European parts of Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine.

There were several camps outside the Soviet Union, in Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, and Mongolia, which were under the direct control of the Gulag.[citation needed]

Throughout the history of the Soviet Union, there were at least 476 separate camp administrations.[123][124] The Russian researcher Galina Ivanova stated that,[124]

to date, Russian historians have discovered and described 476 camps that existed at different times on the territory of the USSR. It is well known that practically every one of them had several branches, many of which were quite large. In addition to the large numbers of camps, there were no less than 2,000 colonies. It would be virtually impossible to reflect the entire mass of Gulag facilities on a map that would also account for the various times of their existence.

Since many of these existed only for short periods, the number of camp administrations at any given point was lower. It peaked in the early 1950s when there were more than 100 camp administrations across the Soviet Union. Most camp administrations oversaw several single camp units, some as many as dozens or even hundreds.[125] The infamous complexes were those at Kolyma, Norilsk, and Vorkuta, all in arctic or subarctic regions. However, prisoner mortality in Norilsk in most periods was actually lower than across the camp system as a whole.[126]

Special institutions

[edit]- There were separate camps or zones within camps for juveniles (малолетки, maloletki), the disabled (in Spassk), and mothers (мамки, mamki) with babies.

- Family members of "Traitors of the Motherland" (ЧСИР, член семьи изменника Родины, ChSIR, Chlyen sem'i izmennika Rodini) were placed under a special category of repression.

- Secret research laboratories known as Sharashka (шарашка) held arrested and convicted scientists, some of them prominent, where they anonymously developed new technologies and also conducted basic research.

Historiography

[edit]Origins and functions of the Gulag

[edit]According to historian Stephen Barnes, the origins and functions of the Gulag can be looked at in four major ways:[127]

- The first approach was championed by Alexander Solzhenitsyn, and is what Barnes terms the moral explanation. According to this view, Soviet ideology eliminated the moral checks on the darker side of human nature – providing convenient justifications for violence and evil-doing on all levels: from political decision-making to personal relations.

- Another approach is the political explanation, according to which the Gulag (along with executions) was primarily a means for eliminating the regime's perceived political enemies (this understanding is favoured by historian Robert Conquest, amongst others).

- The economic explanation, in turn as set out by historian Anne Applebaum, argues that the Soviet regime instrumentalised the Gulag for its economic development projects. Although never economically profitable, it was perceived as such right up to Stalin's death in 1953.

- Finally, Barnes advances his own, fourth explanation, which situates the Gulag in the context of modern projects of 'cleansing' the social body of hostile elements, through spatial isolation and physical elimination of individuals defined as harmful.

Hannah Arendt argues that as part of a totalitarian system of government, the camps of the Gulag system were experiments in "total domination." In her view, the goal of a totalitarian system was not merely to establish limits on liberty, but rather to abolish liberty entirely in service of its ideology. She argues that the Gulag system was not merely political repression because the system survived and grew long after Stalin had wiped out all serious political resistance. Although the various camps were initially filled with criminals and political prisoners, eventually they were filled with prisoners who were arrested irrespective of anything relating to them as individuals, but rather only on the basis of their membership in some ever shifting category of imagined threats to the state.[128]: 437–59

She also argues that the function of the Gulag system was not truly economic. Although the Soviet government deemed them all "forced labor" camps, this in fact highlighted that the work in the camps was deliberately pointless, since all Russian workers could be subject to forced labor.[128]: 444–5 The only real economic purpose they typically served was financing the cost of their own supervision. Otherwise the work performed was generally useless, either by design or made that way through extremely poor planning and execution; some workers even preferred more difficult work if it was actually productive. She differentiated between "authentic" forced-labor camps, concentration camps, and "annihilation camps".[128]: 444–5

In authentic labor camps, inmates worked in "relative freedom and are sentenced for limited periods." Concentration camps had extremely high mortality rates and but were still "essentially organized for labor purposes." Annihilation camps were those where the inmates were "systematically wiped out through starvation and neglect." She criticizes other commentators' conclusion that the purpose of the camps was a supply of cheap labor. According to her, the Soviets were able to liquidate the camp system without serious economic consequences, showing that the camps were not an important source of labor and were overall economically irrelevant.[128]: 444–5

Arendt argues that together with the systematized, arbitrary cruelty inside the camps, this served the purpose of total domination by eliminating the idea that the arrestees had any political or legal rights. Morality was destroyed by maximizing cruelty and by organizing the camps internally to make the inmates and guards complicit. The terror resulting from the operation of the Gulag system caused people outside of the camps to cut all ties with anyone who was arrested or purged and to avoid forming ties with others for fear of being associated with anyone who was targeted. As a result, the camps were essential as the nucleus of a system that destroyed individuality and dissolved all social bonds. Thereby, the system attempted to eliminate any capacity for resistance or self-directed action in the greater population.[128]: 437–59

Archival documents

[edit]Statistical reports made by the OGPU–NKVD–MGB–MVD between the 1930s and 1950s are kept in the State Archive of the Russian Federation formerly called Central State Archive of the October Revolution (CSAOR). These documents were highly classified and inaccessible. Amid glasnost and democratization in the late 1980s, Viktor Zemskov and other Russian researchers managed to gain access to the documents and published the highly classified statistical data collected by the OGPU-NKVD-MGB-MVD and related to the number of the Gulag prisoners, special settlers, etc. In 1995, Zemskov wrote that foreign scientists have begun to be admitted to the restricted-access collection of these documents in the State Archive of the Russian Federation since 1992.[129] However, only one historian, namely Zemskov, was admitted to these archives, and later the archives were again "closed", according to Leonid Lopatnikov.[130] Pressure from the Putin administration has exacerbated the difficulties of Gulag researchers.[131]

While considering the issue of reliability of the primary data provided by corrective labor institutions, it is necessary to take into account the following two circumstances. On the one hand, their administration was not interested to understate the number of prisoners in its reports, because it would have automatically led to a decrease in the food supply plan for camps, prisons, and corrective labor colonies. The decrement in food would have been accompanied by an increase in mortality that would have led to wrecking of the vast production program of the Gulag. On the other hand, overstatement of data of the number of prisoners also did not comply with departmental interests, because it was fraught with the same (i.e., impossible) increase in production tasks set by planning bodies. In those days, people were highly responsible for non-fulfilment of plan. It seems that a resultant of these objective departmental interests was a sufficient degree of reliability of the reports.[132]

Between 1990 and 1992, the first precise statistical data on the Gulag based on the Gulag archives were published by Viktor Zemskov.[133] These had been generally accepted by leading Western scholars,[19][12] despite the fact that a number of inconsistencies were found in this statistics.[134] Not all the conclusions drawn by Zemskov based on his data have been generally accepted. Thus, Sergei Maksudov alleged that although literary sources, for example the books of Lev Razgon or Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, did not envisage the total number of the camps very well and markedly exaggerated their size. On the other hand, Viktor Zemskov, who published many documents by the NKVD and KGB, was far from understanding of the Gulag essence and the nature of socio-political processes in the country. He added that without distinguishing the degree of accuracy and reliability of certain figures, without making a critical analysis of sources, without comparing new data with already known information, Zemskov absolutizes the published materials by presenting them as the ultimate truth. As a result, Maksudov charges that Zemskov's attempts to make generalized statements with reference to a particular document, as a rule, do not hold water.[135]

In response, Zemskov wrote that the charge that he allegedly did not compare new data with already known information could not be called fair. In his words, the trouble with most western writers is that they do not benefit from such comparisons. Zemskov added that when he tried not to overuse the juxtaposition of new information with "old" one, it was only because of a sense of delicacy, not to once again psychologically traumatize the researchers whose works used incorrect figures, as it turned out after the publication of the statistics by the OGPU-NKVD-MGB-MVD.[129]

According to French historian Nicolas Werth, the mountains of the materials of the Gulag archives, which are stored in funds of the State Archive of the Russian Federation and were being constantly exposed during the last fifteen years, represent only a very small part of bureaucratic prose of immense size left over after the decades of "creativity" by the "dull and reptile" organization managing the Gulag. In many cases, local camp archives, which had been stored in sheds, barracks, or other rapidly disintegrating buildings, simply disappeared in the same way as most of the camp buildings did.[136]

In 2004 and 2005, some archival documents were published in the edition Istoriya Stalinskogo Gulaga. Konets 1920-kh — Pervaya Polovina 1950-kh Godov. Sobranie Dokumentov v 7 Tomakh (The History of Stalin's Gulag. From the Late 1920s to the First Half of the 1950s. Collection of Documents in Seven Volumes), wherein each of its seven volumes covered a particular issue indicated in the title of the volume:

- Mass Repression in the USSR (Massovye Repressii v SSSR);[137]

- Punitive System. Structure and Cadres (Karatelnaya Sistema. Struktura i Kadry);[138]

- Economy of the Gulag (Ekonomika Gulaga);[139]

- The Population of the Gulag. The Number and Conditions of Confinement (Naselenie Gulaga. Chislennost i Usloviya Soderzhaniya);[140]

- Specsettlers in the USSR (Specpereselentsy v SSSR);[141]

- Uprisings, Riots, and Strikes of Prisoners (Vosstaniya, Bunty i Zabastovki Zaklyuchyonnykh);[142] and

- Soviet Repressive and Punitive Policy. Annotated Index of Cases of the SA RF (Sovetskaya Pepressivno-karatelnaya Politika i Penitentsiarnaya Sistema. Annotirovanniy Ukazatel Del GA RF).[143]

The edition contains the brief introductions by the two "patriarchs of the Gulag science", Robert Conquest and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, and 1,431 documents, the overwhelming majority of which were obtained from funds of the State Archive of the Russian Federation.[144]

History of Gulag population estimates

[edit]During the decades before the dissolution of the USSR, the debates about the population size of GULAG failed to arrive at generally accepted figures; wide-ranging estimates have been offered,[145] and the bias toward higher or lower side was sometimes ascribed to political views of the particular author.[145] Some of those earlier estimates (both high and low) are shown in the table below.

| GULAG population | Year the estimate was made for | Source | Methodology | ||

| 15 million | 1940–42 | Mora & Zwiernag (1945)[146] | – | ||

| 2.3 million | December 1937 | Timasheff (1948)[147] | Calculation of disenfranchised population | ||

| Up to 3.5 million | 1941 | Jasny (1951)[148] | Analysis of the output of the Soviet enterprises run by NKVD | ||

| 50 million | total number of persons passed through GULAG |

Solzhenitsyn (1975)[149] | Analysis of various indirect data, including own experience and testimonies of numerous witnesses | ||

| 17.6 million | 1942 | Anton Antonov-Ovseenko (1999)[150] | NKVD documents[151] | ||

| 4–5 million | 1939 | Wheatcroft (1981)[152] | Analysis of demographic data.a | ||

| 10.6 million | 1941 | Rosefielde (1981)[153] | Based on data of Mora & Zwiernak and annual mortality.a | ||

| 5.5–9.5 million | late 1938 | Conquest (1991)[154] | 1937 Census figures, arrest and deaths estimates, variety of personal and literary sources.a | ||

| 4–5 million | every single year | Volkogonov (1990s)[155] | |||

| a.^ Note: Later numbers from Rosefielde, Wheatcroft and Conquest were revised down by the authors themselves.[19][65] | |||||

The glasnost political reforms in the late 1980s and the subsequent dissolution of the USSR, led to the release of a large amount of formerly classified archival documents[156] including new demographic and NKVD data.[12] Analysis of the official GULAG statistics by Western scholars immediately demonstrated that, despite their inconsistency, they do not support previously published higher estimates.[145] Importantly, the released documents made possible to clarify terminology used to describe different categories of forced labor population, because the use of the terms "forced labor", "GULAG", "camps" interchangeably by early researchers led to significant confusion and resulted in significant inconsistencies in the earlier estimates.[145]

Archival studies revealed several components of the NKVD penal system in the Stalinist USSR: prisons, labor camps, labor colonies, as well as various "settlements" (exile) and of non-custodial forced labor.[4] Although most of them fit the definition of forced labor, only labor camps, and labor colonies were associated with punitive forced labor in detention.[4] Forced labor camps ("GULAG camps") were hard regime camps, whose inmates were serving more than three-year terms. As a rule, they were situated in remote parts of the USSR, and labor conditions were extremely hard there. They formed a core of the GULAG system. The inmates of "corrective labor colonies" served shorter terms; these colonies were located in less remote parts of the USSR, and they were run by local NKVD administration.[4]

Preliminary analysis of the GULAG camps and colonies statistics (see the chart on the right) demonstrated that the population reached the maximum before the World War II, then dropped sharply, partially due to massive releases, partially due to wartime high mortality, and then was gradually increasing until the end of Stalin era, reaching the global maximum in 1953, when the combined population of GULAG camps and labor colonies amounted to 2,625,000.[157]

The results of these archival studies convinced many scholars, including Robert Conquest[19] or Stephen Wheatcroft to reconsider their earlier estimates of the size of the GULAG population, although the 'high numbers' of arrested and deaths are not radically different from earlier estimates.[19] Although such scholars as Rosefielde or Vishnevsky point at several inconsistencies in archival data with Rosefielde pointing out the archival figure of 1,196,369 for the population of the Gulag and labor colonies combined on December 31, 1936, is less than half the 2.75 million labor camp population given to the Census Board by the NKVD for the 1937 census,[158][134] it is generally believed that these data provide more reliable and detailed information that the indirect data and literary sources available for the scholars during the Cold War era.[12] Although Conquest cited Beria's report to the Politburo of the labor camp numbers at the end of 1938 stating there were almost 7 million prisoners in the labor camps, more than three times the archival figure for 1938 and an official report to Stalin by the Soviet minister of State Security in 1952 stating there were 12 million prisoners in the labor camps.[159]

These data allowed scholars to conclude that during the period of 1928–53, about 14 million prisoners passed through the system of GULAG labor camps and 4–5 million passed through the labor colonies.[19] Thus, these figures reflect the number of convicted persons, and do not take into account the fact that a significant part of Gulag inmates had been convicted more than one time, so the actual number of convicted is somewhat overstated by these statistics.[12] From other hand, during some periods of Gulag history the official figures of GULAG population reflected the camps' capacity, not the actual number of inmates, so the actual figures were 15% higher in, e.g. 1946.[19]

The USSR implemented a number of labor disciplinary measures, due to the lack of productivity of its labour force in the early 1930s. 1.8 million workers were sentenced to 6 months in forced labor with a quarter of their original pay, 3.3 million faced sanctions, and 60k were imprisoned for absentees in 1940 alone. The conditions of Soviet workers worsened in WW2 as 1.3 million were punished in 1942, and 1 million each were punished in subsequent 1943 and 1944 with the reduction of 25% of food rations. Further more, 460 thousand were imprisoned throughout these years.[160]

Impact

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2010) |

Culture

[edit]The Gulag spanned nearly four decades of Soviet and East European history and affected millions of individuals. Its cultural impact was enormous.

The Gulag has become a major influence on contemporary Russian thinking, and an important part of modern Russian folklore. Many songs by the authors-performers known as the bards, most notably Vladimir Vysotsky and Alexander Galich, neither of whom ever served time in the camps, describe life inside the Gulag and glorified the life of "zeks". Words and phrases which originated in the labor camps became part of the Russian/Soviet vernacular in the 1960s and 1970s. The memoirs of Alexander Dolgun, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Varlam Shalamov and Yevgenia Ginzburg, among others, became a symbol of defiance in Soviet society. These writings harshly chastised the Soviet people for their tolerance and apathy regarding the Gulag, but at the same time provided a testament to the courage and resolve of those who were imprisoned.

Another cultural phenomenon in the Soviet Union linked with the Gulag was the forced migration of many artists and other people of culture to Siberia. This resulted in a Renaissance of sorts in places like Magadan, where, for example, the quality of theatre production was comparable to Moscow's and Eddie Rosner played jazz.

Literature

[edit]Many eyewitness accounts of Gulag prisoners have been published:

- Varlam Shalamov's Kolyma Tales is a short-story collection, cited by most major works on the Gulag, and widely considered one of the main Soviet accounts.

- Victor Kravchenko wrote I Chose Freedom after defecting to the United States in 1944. As a leader of industrial plants he had encountered forced labor camps in across the Soviet Union from 1935 to 1941. He describes a visit to one camp at Kemerovo on the Tom River in Siberia. Factories paid a fixed sum to the KGB for every convict they employed.

- Anatoli Granovsky wrote I Was an NKVD Agent after defecting to Sweden in 1946 and included his experiences seeing gulag prisoners as a young boy, as well as his experiences as a prisoner himself in 1939. Granovsky's father was sent to the gulag in 1937.

- Julius Margolin's book A Travel to the Land Ze-Ka was finished in 1947, but it was impossible to publish such a book about the Soviet Union at the time, immediately after World War II.

- Gustaw Herling-Grudziński wrote A World Apart, which was translated into English by Andrzej Ciolkosz and published with an introduction by Bertrand Russell in 1951. By describing life in the gulag in a harrowing personal account, it provides an in-depth, original analysis of the nature of the Soviet communist system.

- Victor Herman's book Coming out of the Ice: An Unexpected Life. Herman experienced firsthand many places, prisons, and experiences that Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was able to reference in only passing or through brief second hand accounts.

- Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's book The Gulag Archipelago was not the first literary work about labor camps. His previous book on the subject, "One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich", about a typical day in the life of a Gulag inmate, was originally published in the most prestigious Soviet monthly, Novy Mir (New World), in November 1962, but was soon banned and withdrawn from all libraries. It was the first work to demonstrate the Gulag as an instrument of governmental repression against its own citizens on a massive scale. The First Circle, an account of three days in the lives of prisoners in the Marfino sharashka or special prison was submitted for publication to the Soviet authorities shortly after One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich but was rejected and later published abroad in 1968.

- Slavomir Rawicz's book "The Long Walk: The True Story of a Trek to Freedom": In 1941, the author and six other fellow prisoners escaped a Soviet labor camp in Yakutsk.

- János Rózsás, a Hungarian writer, often referred to as the Hungarian Solzhenitsyn,[161] wrote many books and articles on the issue of the Gulag.

- Zoltan Szalkai, a Hungarian documentary filmmaker, made several films about gulag camps.

- Karlo Štajner, a Croatian communist who was active in the former Kingdom of Yugoslavia and the manager of the Comintern Publishing House in Moscow 1932–39, was arrested one night and taken from his Moscow home after being accused of anti-revolutionary activities. He spent the next 20 years in camps from Solovki to Norilsk. After USSR–Yugoslavian political normalization he was re-tried and quickly found innocent. He left the Soviet Union with his wife, who had been waiting for him for 20 years, in 1956 and spent the rest of his life in Zagreb, Croatia. He wrote an impressive book titled 7000 days in Siberia.

- Dancing Under the Red Star by Karl Tobien (ISBN 1-4000-7078-3) tells the story of Margaret Werner, an athletic girl who moves to Russia right before Stalin came to power. She faces many hardships, as her father is taken away from her and imprisoned. Werner is the only American woman who was held in the Gulag to tell about it.

- Alexander Dolgun's Story: An American in the Gulag (ISBN 0-394-49497-0), by a member of the US Embassy, and I Was a Slave in Russia (ISBN 0-8159-5800-5), an American factory owner's son, were two more American citizens interned who wrote of their ordeal. They were interned due to their American citizenship for about eight years c. 1946–55.

- Yevgenia Ginzburg wrote two famous books about her remembrances, Journey Into the Whirlwind and Within the Whirlwind.

- Savić Marković Štedimlija, a pro-Croatian Montenegrin ideologist. Caught in Austria by the Red Army in 1945, he was sent to the USSR and spent ten years in the Gulag. After his release, Marković wrote his autobiographical account in two volumes titled Ten years in Gulag (Deset godina u Gulagu, Matica crnogorska, Podgorica, Montenegro 2004).

- Anița Nandriș-Cudla's book, 20 Years in Siberia [20 de ani în Siberia] is the own life's account written by a Romanian peasant woman from Bucovina (Mahala village near Cernăuți) who managed to survive the harsh, forced labor system together with her three sons. Together with her husband and her three underage children, she was deported from Mahala village to the Soviet Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug, at the Polar Circle, without a trial or even a communicated accusation. The same night of June 12 to 13, 1941, (that is, just before Germany's invasion of the USSR), overall 602 fellow villagers were arrested and deported, without any prior notice. Her mother received the same sentence but was spared from deportation after the fact that she was a paraplegic was acknowledged by the authorities. It was later discovered that the reason for her deportation and forced labor was the fake and nonsensical claim that, allegedly, her husband had been a mayor in the Romanian administration, a politician and a rich peasant, none of the latter of which was true. Separated from her husband, she brought up the three boys, overcame typhus, scorbutus, malnutrition, extreme cold and harsh toils, to later return to Bucovina after rehabilitation. Her manuscript was written toward the end of her life, in the simple and direct language of a peasant with three years of public school education, and was secretly brought to Romania before the fall of Romanian communism, in 1982. Her manuscript was first published in 1991. Her deportation was shared mainly with Romanians from Bucovina and Basarabia, Finnish and Polish prisoners, as token proof to show that Gulag labor camps had also been used for the shattering/ extermination of the natives in the newly occupied territories of the Soviet Union.

- Frantsishak Alyakhnovich – Solovki prisoner